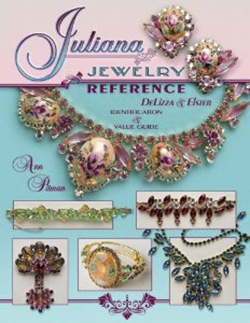

Juliana Jewelry Reference by Ann Pitman

March 28, 2013

I have vivid childhood memories of looking through my mother’s jewelry box and being transfixed by her floating opal earrings. Time seemed to stand still as I turned them over and over to see their fascinating displays of color and motion. Recently, after purchasing an enchanting double floating opal necklace, I found myself transfixed once again. And I began to wonder: who had created such an intriguing and unusual form of jewelry, and when was it first made? Little did I know that finding the answers to those simple questions would take months of research, and would lead to the discovery of a quite remarkable and nearly forgotten story.

Appearing much like a miniature snow globe, the floating opal is essentially comprised of small chips of opal encased in a liquid-filled glass orb. Although floating opals are still manufactured today, the jewelry we recognize as vintage reached the peak of its demand in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Surprisingly though, it was decades earlier that the floating opal was first introduced. And remarkably, its inventor was not a jeweler, but a 50 year-old, Stanford educated, patent-holding mechanical engineer. Beginning in 1920, in a venture that would take him through the rest of his life, Horace H. Welch patented, perfected, manufactured, and marketed his invention transforming it, and himself, along the way.

HORACE H. WELCH: MECHANICAL ENGINEER/INVENTOR

Horace Herbert Welch was born in 1871, the second son of a country doctor, in La Cygne, Kansas. By 1900, much of his family had relocated to Los Angeles. Welch attended Harvard College for a year, but actually graduated from Leland Stanford Junior University in 1897 with an A.B. degree in physics. Little is known of his life from that time until August 1910, when at the age of 39 he filed the application for his first patent for a “Speed Indicator.” In the following years through 1920, Welch applied for no less than 13 mechanical and electrical patents from various locations including Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Milwaukee.

The only known photograph of Horace Herbert Welch, taken when he was a very young man.

That Welch was an intelligent man is without question. One has only to read the multitudinous pages of his 24 known patents to observe his quite brilliant and meticulous mind. His dramatic pen style also revealed a great capacity for showmanship and promotion – qualities that would serve him well in the jewelry industry. Because he never married and lived so far away from his California relatives, living family members know little of him but do report that the family considered him eccentric.

One has to wonder what would prompt a man, whose previous patents included carburetors, speedometers, fuel indicators, an early car alarm, and a mechanical pencil, to invent and patent a process for manufacturing jewelry. Was it a mid-life crisis? Was it a woman? The truth is that we may never know. What is known is that within two years of receiving his first patent for what would become the floating opal, Horace Welch left a successful career in Chicago and moved to New York City to begin manufacturing and selling his “Gem.”

WELCH’S PATENTS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE FLOATING OPAL

For an accurate picture of the development of “The Floating Opal,” it is best to look at Welch’s patents in the order that they were filed rather than when they were issued. His first application for what would become the floating opal was filed in January of 1921, and was entitled simply “Gem.” It was approved swiftly by U.S. patent standards in June of 1922.

The patent was very general in nature and consisted of a single page of drawings and two and a half pages of description. In flowery language, Welch wrote that his invention pertained “to a novel and pleasing type of gem or jewel adapted for many and varied uses, particularly in the production of jewelry.” He mentioned opals only twice, and described instead that the shell could be filled loosely with “the well-known sparkling granular ‘metallics’ of the trade, or…crumpled pieces of gold leaf, tinsel or the like.” He stated that the jewelry could be made with or without liquid using a single loose gem or a number of display elements, and he included the rather impractical examples of a ring and a strand of beads.

Even before the patent was granted, a May 1922 publication of The Stanford Illustrated Review noted its alumnus as follows:

Sometime in the year and a half between his patent application and that publication, Welch’s tinsel-filled novelty had made the leap toward becoming a floating opal. Just how he came to conclude that opal fragments should be the display elements is hard to guess. The opal, with its history of being both prized and shunned, was enjoying a new wave of popularity, and owing to its fragility, fragments were “common and of low cost.” Whatever it was that led Welch to the opal, his subsequent applications exhibit a definite shift in focus and a significant concentration on displaying the opal’s colors most advantageously.

However, there were apparently initial production problems related to the gem’s fragility and its tendency to break. In August and November of 1924, Welch filed his second and third patent applications, in which he detailed the necessary improvements and provided many specific enhancements. In contrast to the first, these applications were quite voluminous and present strong evidence that Welch had become concerned with protecting his invention. Although he offered a multitude of variables, several essential elements emerged that came to comprise the floating opal as we know it today.

Most importantly and in simple form, those elements were:

2. The method for constructing a second smaller chamber above the main display chamber that allowed the liquid to expand, and served to trap the bubble where it could be hidden. (Ever the engineer, Welch referred to this two-chamber model as “double globular.”)

3. The introduction of glycerin as the liquid suspension. While Welch stated that a variety of liquids could be used, he concluded that glycerin enhanced the brilliance of the opals, provided the ideal viscosity, and acted as a preservative. (Research confirms that glycerin was, and is, the industry standard liquid suspension in floating opals.)

4. The preference for using the relatively new invention of Pyrex® glass as the housing. Not only did Pyrex® provide a stronger housing, but when used in combination with glycerin (which has a similarly high refractive index), the two virtually disappeared to produce the “illusion of a unitary large opal.”

Welch’s second and third applications did not enjoy the same swift approval as his first. Apparently, at the request of the Patent Office, Welch filed yet another application in November of 1925. That fourth application was a division of his still pending second application. (A division is usually requested when an application contains too many ideas.) Other patent struggles were revealed in a 1929 U.S. Court of Claims ruling, which disclosed that the Patent Office had rejected some of Welch’s claims and denied his subsequent appeals. That 1929 ruling reversed the Patent Office’s denial and in the following three years, Welch’s pending applications were finally approved.

H. H. WELCH: JEWELER

Eight years after his first floating opal patent, 1930 census data showed Welch living in Manhattan. At age 59, his occupation was listed as “jeweler.” His transformation was complete. He had chucked his engineering career to embrace his jewel invention. Somehow, even with a deepening depression of the economy and several patents still pending, he had managed to successfully produce, promote and sell the floating opal.

By all accounts, the H. H. Welch Company was a modest operation, and it is likely that Welch produced many of the floating opals himself. Welch enjoyed success selling his invention to jewelry stores nationwide and he continued to promote it as a “new jewel” well into the 1930s. His final floating opal patents were issued in 1931 and 1932, and there was another big promotional push at that time. Probably as a result of the Great Depression, demand seems to have dampened by the late 1930s, and the ads and articles appeared less frequently.

CONFLICTS WITH CORO AND EXPIRING PATENTS

Welch continued to produce floating opals until his unexpected death in 1947. The early 1940s had not been without challenge for the inventor. As early as 1943, Coro began advertising a line of “genuine floating opals” and Welch sued for patent infringement. Sadly, the suit was not settled until 1951, and Welch did not live to see it. After his death, his brother and nephew spent months in New York working to settle the estate. They sold the business to Robert Rose and as late as 1966, H. H. Welch, Inc. was still listed in the Jewelers’ Circular Keystone as a supplier of floating opal jewelry.

Prior to that, in 1949, 27 years after the floating opal’s first appearance, Welch’s final patent expired. This left a door open to any and all manufacturers, and they did not hesitate to step through. Newer technology allowed faster production and floating opals soon inundated the market. No longer limited to jewelry stores, this type of jewelry was widely available in department stores across the U.S. Perhaps remembering their mothers’ floating opals, women embraced this “new” jewel with zeal. Floating opal jewelry became a popular bridal accessory, and many wedding announcements included statements like, “the bride’s only jewelry was a floating opal pendant,” or “the bride wore a pair of floating opal earrings, a gift from the groom.”

Although Welch had no way of knowing that his floating opal would continue to be appreciated, coveted and manufactured into the 21st century, it is evident that he knew it was something quite extraordinary. Using his scientific knowledge, keen mechanical mind and dogged persistence, he combined glass, glycerin, and some broken opals to construct an enchanting new jewel. The Floating Opal was his masterpiece and its creation showed that this eccentric engineer held the heart of an artist.

IDENTIFYING, DATING AND ASSESSING WELCH’S FLOATING OPALS

Welch’s floating opal pendants* can be identified and dated by the markings on their decorative caps. (Necklace chains should not be used for identification purposes as they were often supplied by the retailer.) All of Welch’s early pendants were set in fine gold and the gold content (14K or 18K) is marked on the cap. The early caps are also marked with patent information and that is how they can be dated.

The Cap Markings:

- Caps marked “PAT. 6.27.22” date from 1922 to 1924. These are the earliest and rarest due to their flaw-inherent construction.

- Caps marked “PATS. PEND.” were probably manufactured between 1925 and 1931. Welch would have used this mark to protect the improved model as he waited for his second, third and fourth patents.

- Caps marked “PAT. 10.13.31” were made after Oct. 13, 1931 and perhaps well into the 1930s.

- Caps marked simply “PAT.” most likely date after the final patent date of March 22, 1932.

One of Welch’s most beautiful creations: a double pendant floating opal necklace. Note the Art Deco style filigree lariat finding. Each pendant is typical size at 7/8 of an inch (22 mm) long. The caps are marked at the top: 14K and “PATS. PEND.”

It is very probable that Welch’s floating opals continued to be marked with some form of patent information until 1949, when the last patent expired.

(*Author’s note: I have never seen a floating opal ring although jewelry store ads indicate that they were manufactured through the early 1930s. I assume that they too, would have been marked with patent information.)

Another Surprise – Invisible Solids

In Welch’s third patent application, I was surprised to discover that he recommended adding “invisible solid parts,” in the form of bits of Pyrex® glass, to the opal chips. He stated that this addition decreased the cost and that because the parts essentially became invisible, they spaced the gems and improved their beauty by “increasing the number of reflecting gem surfaces.” Close examination does confirm “invisible” bits of Pyrex glass floating among the opals. I am hopeful that invisible solids were exclusive to Welch’s jewelry and will provide an additional way to identify his pieces. (I do not see any invisible solids in my mother’s floating opal earrings, which were made by Opalite.)

One of the earliest known floating opal pendants set in 14-karat white gold. It is shown on black cord as many early floating opals were worn. This pendant has suffered damage: note the large bubble and the discolored glycerin.

A Note About the Bubble

To many eyes, the bubble is a flaw and the truth is that Welch felt the same way. With his “double globular” design, Welch was able to hide the bubble under the pendant cap (he used another method for rings). In addition, he attempted to make the passage between the two chambers narrow enough to keep the bubble in the top chamber and thus prevent “the evil appearance of the otherwise useful air space.”

Current belief is that any bubble in a floating opal reflects damage and detracts from the value. While a very large bubble is an indication of leakage and should be avoided, I would argue that in these early pieces, the theory of trapping the bubble was probably much easier than the actual practice. As handmade jewelry, floating opals suffer the “human touch” and are all the sweeter for it. Although attempts were made to keep it from sight, many a bubble has escaped its chamber and can be seen when a pendant is lying prone or held inverted. It is important to remember that many pendants are close to 90 years old, and the fact that they survived at all should weigh heavily in their favor.

CARING FOR YOUR VINTAGE FLOATING OPALS

Although they are remarkably sturdy for glass, floating opals can suffer damage. Follow these hints for storage and care to keep floating opals in nice condition:

- To avoid breakage, store floating opals in a padded box separate from other jewelry.

- To prevent a bubble from escaping its hidden chamber, try to store pendants in an upright position.

- Avoid temperature extremes like those found in attics or unheated basements. It’s also wise to avoid shipping floating opals in the heat of summer and the cold of winter.

- Surface cleaning can be done with a mild detergent solution using cotton swabs or a soft cloth. Submerging a floating opal in any type of liquid is not recommended. Do not use harsh chemical solvents or abrasives as they might scratch the glass or damage the mounting.

Jewelry photography by Gary Simmons

Welch portrait courtesy of Nancy Rowan

Patent Illustrations shown in the gallery linked below are from the U.S. Patent website

To view more pictures from this article click here.