The Enchanting Jewelry of Wendy Gell

May 23, 2014

Past CJCI Speakers

July 6, 2014Marcel Boucher was an unbelievably talented jeweler. Not just a designer, but a jeweler/model maker. He owned a 10,000 square foot factory on the tenth floor at 304 E. 23rd St. in Manhattan, and he was a perfectionist. Boucher was, in fact, so discouraged with designs of his being copied that he had a stone manufacturer make cabochon stones exclusively for him in special sizes unavailable to anyone else

As Sandra Boucher said in a previously-published interview shared online , “Although the pirates could buy a casting and copy it, they could not get stones to fit: ‘These they can never copy-they are only for us’.”

And I can tell you this is true. I have owned a Boucher sterling cabochon pin-clip (also known as a fur clip) for 10 years and have never been able to find coral cabochon stones to replace the missing ones!

Boucher Fruclip Missing Cabochon Stones – The only way to repair this is to cannibalize an existing piece of Boucher with the same size cabochons that were made exclusively in sizes just for him. Although the pirates could buy a casting and copy it, they could not get stones to fit: “These they can never copy-they are only for us,” Sandra Boucher remembers him exclaiming.

His factory had its own white metal for casting the jewelry in addition to making the molds, setting the stones, polishing and packing the jewelry. They had a production floor, and he used incredible German model makers trained in fine jewelry that worked very closely with him because they were the best and understood the exacting specifications that he required for his jewlery. It was important to Marcel that his designs were exclusive, which is one of the reasons it seems so absurd to suggest that Reinad was commissioned to make any jewelry bearing his name. But the Bouchers weren’t the only ones disgusted by “style pirates” or the only parties trying to prevent period copies.

Pursuing Patents of Jewelry Designs

Starting in the late 1930s, you can trace the costume jewelry companies as they started to issue patents to protect their designs. It took time, (and a great deal of money) to patent their designs against “style pirates” (the actual term used in the costume jewelry industry for those who blatantly copied other manufacturers) – the companies that were waiting in the background to make a cheap copy of a high end piece of jewelry at a low price point so a secretary shopping at Woolworth or a lower end store could have the latest style of fashion jewelry society ladies were buying at Saks Fifth Avenue. Many wealthy women wore costume jewelry even though they could afford the real thing. They were building a jewelry wardrobe, the same way we do today. Unfortunately, the patenting process was very time consuming and costly. It could take three months or more (some records show patents were pending for a year before they were approved) and they cost about $60 or so then – a great deal of money when you were producing hundreds of designs. Many companies, especially smaller ones, did not avail themselves of patents, so they had no recourse when their beautiful designs were taken.

Unsigned Period Copy of Trifari – This is a copy of Trifari’s knockoff of Chanel Gripoix jewelry. This is found in different colors, with varying numbers of flowers matching the other Trifari patents (there are two, three, and five flower versions). Some have center rhinestones, others have pearls. Since they were patented by Trifari in 1941 and all of the unsigned ones share the same fur clip back that is NOT Trifari’s, I suspect Reinad or some other jobber made these. I also have in my files a piece that was clearly made from a Trifari mold because it says PAT PEND, but the letters are RAISED instead of incised like the original would be since it is reversed when a mold is made.

Utility patents (for how something works) such as an ear clip finding, or a brooch mechanism, were good for 20 years, but most design patents (for how something looks) lasted only about for about three and a half years. In the fashion world, that equates to a lifetime. Each company produced several lines a year, and by the time a piece was put into production, they were on to the next line, and the next season. Jewelry does not exist in a vacuum. It was designed to go with the fashions of the day. A changing neckline or a lighter fabric dictated the kind of jewelry that was designed.

How “Jobbers” Fit In

A different situation occurred with jewelry created by jobbers. These manufacturers made product lines that were bought by many companies. For example, Kramer, Hattie Carnegie, Christian Dior, and Weiss are several of the many companies that did not manufacture their own jewelry. They had outside sources make their product for them.

There are also companies such as Hollycraft who produced styles for Weiss but in exclusive colors just for them. Some companies had their own designers work with jobbers to make exclusive designs for them. Other times smaller companies would come in to a showroom, pick certain styles that were in a line, and order them in exclusive colors with their names stamped into the design. So there were pieces signed with a certain name, and a very similar style might be sold unsigned to stores and sold on cards or in boxes with the store name.

For instance, there are Hattie Carnegie and Kenneth Jay Lane pieces that look similar because Kenneth Jay Lane originally designed some jewelry for Hattie Carnegie that were likely made by the same jobber. There is also a well known signed Hattie Carnegie trembler fly that also appears signed Pauline Rader and unsigned too (I own the unsigned version) as another example. No doubt it was made by the same manufacturer.

It doesn’t mean these are copies trying to cash in on a famous name in these cases. This was a business practice used by many companies who just did not have their own manufacturing capabilities. These are different than period copies. Fallon & Kappel, a very high end manufacturer, originally produced the best and earliest Hattie Carnegie jewelry marked HC in a diamond and did work for a few other clients. They also produced some of the best and most collectible Eisenberg jewelry and eventually, Eisenberg became their sole client.

Who Was Patenting and Who Was Suing?

A company like Coro (who ironically had the most patents issued), thought nothing of copying another company’s designs such as DuJay’s very popular Rickshaw carrier, monkey climbing a coconut tree, and a gorgeous pavé rose. They were sued by Marcel Boucher and probably others as well. When you look at the history of patents filed by Trifari and Coro, many of them are so similar you have to wonder if they were spying on one another. Marcel Boucher once said he never wanted to be a big company like Trifari, because if he had one bad year, it could put him out of business. And that is very true. It also cost a fortune to bring forth a lawsuit as he did against Coro which awarded him $35,000, but it cost $50,000 in legal fees. That was a tremendous amount of money in that day.

Coro, the largest costume jewelery manufacturer in the world, as well as holder of the most patents of any costume jewelry company was not above copying other high end makers and at times being sued in the process as in the case with Marcel Boucher suing them for design infringement. One only has to compare Coro patents to Trifari patents of the same time frame to see how similar both companies designs at times were, but by changing just a few design elements, could be considered a “unique” design and have the patents approved. Coro copied some of DuJay’s most beautiful designs such as this rose, the DuJay Rickshaw, the DuJay monkey climbing the coconut tree, another hanging monkey, and likely others. Since DuJay did not patent their jewelry until 1939, my stunning unsigned DuJay fur clip is probably a few years earlier. In 1940 Coro patented their own version (shown at right) very much like DuJay’s, and the patent drawing reveals the completely pavéd rose with enamel leaves. However, they continued making it through WWII in sterling rose gold vermeil, with less rhinestones. Patent dates are the earliest you can date a piece, but a design patent was good for 3 1/2 – 7 years, and Coro was known for making some of their most popular designs such as the Carmen Miranda bracelet all the way from 1938 through a version signed Vendome in the 1960s. They also made their Quivering Camellia Duette from its earliest form with two dress clips up to a later version using fur clips when dress clips became less popular. The Coro pavé and enamel version patented in 1940 can be seen in Brunialti’s Tribute to America on page 70. The rose itself resembles the DuJay version, but it is not as beautiful on the whole. Reinad also copied this rose marked with the script Chanel signature. See it incorrectly identified as Chanel in “Jewelry by Chanel” by Patrick Mauries on page 93.

Like most of the jewelry of DeRosa and Réja, where we know so many designs exist and are advertised but very few were actually patented, the artistry was not protected. Boucher had about 95 patents, and that includes the double-clip mechanism that he did while working for Mazer, along with a group of rings that he was going to produce in fine jewelry but someone stole the designs before he ever had a chance to make them himself and he was just unbelievably angry over the unfairness of it. DuJay did not patent or even sign their jewelry until 1939 when they finally sued Déja for trademark infringement because they felt their moniker was too similar to their name. DuJay won the case in 1940 causing Déja to change their name to Réja.

Compared to Trifari and Coro, who were responsible for most of the jewelry patents, many companies could just not afford to protect their designs. Patenting took too much time, and it was not cost effective. Also, in order to be covered for patent protection, a design must be unique enough to get the patent. There were ways for other companies to change a design just enough to get a similar one approved. And there were also ways to change the design just enough to get around being sued by a company who had a patent (like the boatload of copies of the Dujay dutch boy and girl twins that show up online almost daily. I can’t even imagine how many of them were made).

This is how beautiful designs by these high end companies wound up (usually unsigned) being produced in cheaper versions we reference as period copies today. It appears that Reinad is one of the few companies that put their names to these pieces, and it’s presumably because they did not fear being sued due to the timeframe in which they made the jewelry, or who they were up against.

The Advent of Copyrights and Calling out the “Style Pirates”

What is absolutely fascinating as a jewelry historian is reading all of the old newspaper articles on costume jewelry over the years. There were stories constantly being written in the women’s or style sections interviewing fine and costume jewelry designers, discussing the trends that were going on, and many editorials (not advertisements) photographed with models wearing the fashions and the jewelry along with them.

On July 4, 1952 there was an interview in the Pittsburgh-Post Gazette with a costume jewelry designer named Michael Paul. Very little is known about him today but some of his jewelry marked with his name appears in advertisements sold at very nice department stores along with Hattie Carnegie and Trifari Jewelry in the late 1940s and early 1950s. However, in 1952 he was a designer for Marvella, and the writer of the article went up to the showroom to meet with him and discuss the jewelry they were doing going forward for the year.

The writer proceeds to discuss some of the favorite pieces she got to see and wanted to take photographs of for the article. She writes, “Michael was hesitant, since they could be copied easily.” So even in 1952, a designer for a major jewelry company such as Marvella would not allow pictures of their jewelry in their showroom to be photographed for fear they would be copied and sold before Marvella’s hit the market.

From July, 1954 up until April, 1955, interviews with Carl Fishel, President of Trifari, appeared in newspapers around the country. At that time they were already in court pursuing copyrights against the “style pirates” that he felt were the bane of the industry, an industry worth $500 million in sales to the American consumer at that point in time. This really puts into perspective the kind of monetary volume the costume jewelry industry was worth in sales in the 1950s. Even today half a billion dollars is big industry!

“Costume jewelry is made to sell. A style pirate merely buys it and copies it,” as he said in one of the mid-1950s articles. The article goes on to say, “All a design pirate has to do … is buy a piece of expensive costume jewelry in a retail store, make a cheap cast of it and start turning out copies overnight. Now, we’re stamping every piece of our jewelry with a copyright sign, so copyists can’t claim they didn’t know it was copyrighted. We’re testing this out in the courts, and we’ll see how it works”. (Jewelry designer Ruth Kamke confirmed this process in an interview, as did Sandra Boucher in another independent interview.)

Obviously Trifari’s “test” did work, because Trifari won their lawsuit against Charel on November 9, 1955. Judge Alexander Bicks ruled “that costume jewelry is a work of art,” not subject to cheap imitations, and that original designs could be registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Trifari never submitted a patent again and went strictly to copyrights, as did most of the costume jewelry industry. It was faster, cheaper, and almost instantaneous. Plus, copyrights last for 25 years where design patents lasted between three and seven years, but most designs were for one season only. Coro was actually one of the few costume jewelry companies that continued to use patents, and they did so up until 1965. But even fine jewelry companies such as David Yurman, Bulgari, and others continue to submit their designs for patent protection.

Modern Day “Style Pirates”

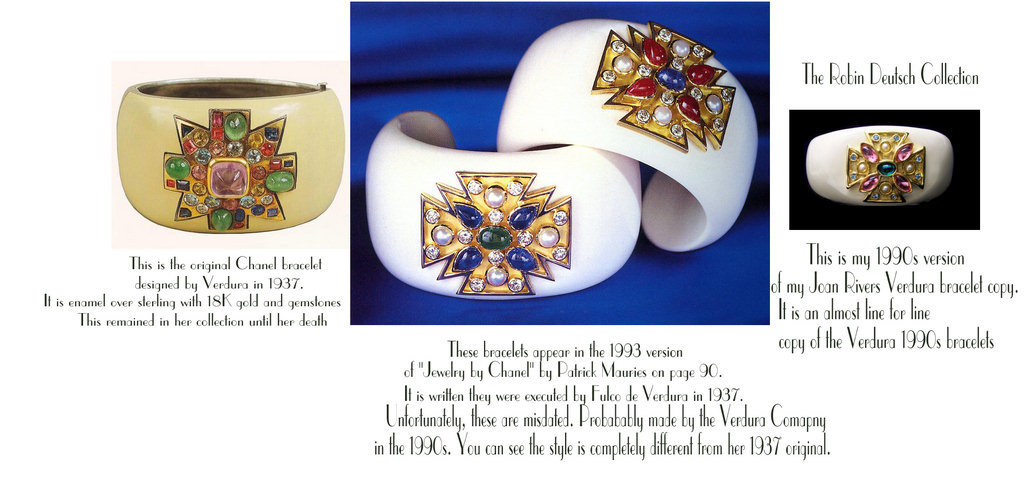

In a New York Times article dated November 22, 1998, there is a story about Joan Rivers jewelry she was designing for QVC, the home shopping network where she still markets jewelry today. It mentions how some of her jewelry is inspired by Verdura (in fact, she did a very close copy of the Chanel Verdura Maltese Cross bracelet).

“Ms. Rivers readily acknowledges the influence and said she enjoys educating her audience about Verdura. ‘I go through the whole history,’ she said. ‘Chanel is Verdura. Let’s all get real here. When things still work 60 years later, that’s when you know they’re great.’”

Chanel-Verdura-Joan Rivers – The first bracelet on the left is Coco Chanel’s orginal maltese cross bracelet designed for her by Verdura. There was another one in a slightly different shape that she wore on her opposite wrist. The center bracelets are a pair of 1980s-1990s inconic Verdura cocholong cuffs. The Joan Rivers one on the right she had copied from her own piece (like the middle style) when she was gifted one by QVC after reaching a certain amount of sales for the many years she was selling jewelry. I own 4 of them and they are one of the most gorgeous bracelets she ever made.

Ward Landrigan, owner of Verdura, was not pleased by Ms. Rivers’s appropriation, especially, he said, when he hears customer complaints like this: “I don’t want the woman who’s doing my nails to be wearing earrings like mine.” But he remains philosophical, “It’s been going on forever, even in Verdura’s day,” he said. “If you’re copied in the fashion or jewelry world today, you have to take it as a compliment.”

So here we are in 2014, when Kenneth Jay Lane is still copying everyone and he even acknowledges this by saying “you’re not anybody unless I have copied you.” Where women still clamor for his costume jewelry and the vintage companies that came before, there will always be copies. Some will be of the highest caliber, and some will be very inexpensive and cheaply made, but as long as women love and adore jewelry, as long as they want to adorn themselves, as long as they covet the expensive pieces they may never be able to own, there will always be copies.

Robin Deutsch has been a jewelry historian and collector since the 1990s. She specializes in American and European costume jewelry, anything from Edwardian to made yesterday. She is a member of many fine and costume jewelry organizations, and she also has her own website on the German jewelry company Knoll & Pregizer which she published in 2009, bringing to the forefront the name and history of this company that was lost to posterity. She was also a lender to the museum exhibit “Finer Things” at Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens, Akron, Ohio, April-October 2012.