Beyond Dior: The Jewelry of Jean-Louis Scherrer by Karin Zwaneveld for CJCI

June 20, 2015

Speakers for CJCI Convention 2016

May 28, 2016Review by Troy Segal

When people ask me “Why do you love vintage jewelry?” I say: because every piece tells a story. It’s a window into a past world, with a frame gold or silver or platinum and panes of precious stones, offering a tiny, glittering glimpse into a time, place, or culture far away (yet sometimes, tantalizingly familiar). What a delight to discover that C. Jeanenne Bell shares my feeling. Else why would so much of her book Answers to Questions About Old Jewelry 1840-1950 (Krause Publications), contain so much engaging social and sartorial history?

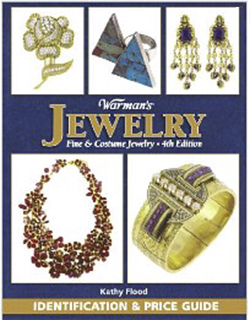

Not that the latest edition of this paperbound guide lacks the solid resource material that’s made it such a valuable reference for both fine and costume jewelry over the years. It’s all (still) here, the meat-and-potatoes data for dealers and collectors: tips for dating pieces, definitions of metals and materials, gem authenticity tests, photos of manufacturing processes, brief bios of makers and designers and facsimiles of their marks (a feature which alone makes the book worth its purchase price for many).

But the heart of Old Jewelry—over three-fourths of its 400 pages—lies in the history, in the parsing of period styles from the mid-19th century on. Bell begins each chapter with an overview of a 20-to-30-year era, and the major events that characterized it, primarily in England and America, though there are references to Europe, too. There’s often a page devoted to a particularly influential event, like the 1876 Centennial International Exposition (a birthday party the U.S. threw for itself, in the shape of a world’s fair, that introduced Americans to a variety of foreign cultures), or an arts movement, such as Art Deco. Bell then focuses on clothing trends, because “it is impossible to fully understand jewelry styles without relating them to the fashions they accessorized,” quoting liberally from magazines and periodicals of the day, from the Godey’s Lady’s Book to Business Week. Each chapter also includes a section on particularly popular and stones and materials; there’s also a sort of cheat sheet of characteristic motifs and materials for each period at the back of the book.

Victorian signed Foster & Bailey gold filled jeweled lion head figural bracelet. Red ruby paste eyes and green emerald paste mouth. Maker marked “F&B” inside. Foster & Bailey – Providence, Rhode Island. 1878-1898. Jewelry courtesy of Sunday and Sunday Antiques on RubyLane.com

Color pictures and illustrations are sprinkled throughout. Bell nails just about every major design, though I was a trifle surprised that the 1890-1917 chapter didn’t mention the garland style so prevalent during the Edwardian Era, especially since it discusses in depth the contemporaneous Art Nouveau, whose bold colors and sinuous, asymmetrical lines stood in deliberate contrast to garland’s white-on-white formality and frothiness. However, the eighth edition does sport a whole new chapter covering Bakelite, Mexican silver, and costume pieces and other collectibles.

The fashion material is especially fascinating. I always knew that clothing and jewelry styles parallel each other, but it’s interesting to see how one literally shaped or influenced the other. Why do so few earrings from the 1840s-50s survive? Partly because they weren’t being made, having been outmoded by current hairstyles and headwear: “Throughout this period, women kept their ears covered. During the day, they were hidden under a bonnet; for evening, they were covered with clusters of curls,” Bell writes, quoting a Godey‘s pronouncement: “We give up the ear.” Why, after World War II, did pieces become so oversized, in the style known as Retro Modern? Because larger proportions—“ear muff” earrings, massive cocktail rings, chunky bracelets—were needed to balance out the long full skirts and exaggerated silhouettes that characterized the reigning New Look, introduced by Christian Dior in 1947, in women’s clothing.

Tracking the trends also proves that even the hottest new style is old. Think it’s au courant to wear a bevy of bracelets and bangles on one arm? They were the latest thing back in 1850 (compensating for giving up the ear and earrings, no doubt). And the current fad for huge costume pieces that flaunt being fake? Been there, did that in the Roaring ‘20s, when designers like Coco Chanel were creating “jewelry so gargantuan and blatant that there is not the smallest pretense it is genuine,” to quote a 1928 story in The Delineator magazine.

Vintage Japanese Toshikane Seven Gods of Fortune (“Immortals”) sterling silver necklace. Hallmarked “Silver” on the back. Circa 1950s. Jewelry courtesy of Sunday and Sunday Antiques on RubyLane.com

Each chapter concludes with an illustrated “Price Guide” to jewelry of that era—a photo gallery of pieces, captured loving close-up (and often including both front and back views, for you let’s-see-the-construction types). And honestly, interesting as the historical text is, the photography’s the thing. Perusing page after page of the gorgeous array, I wanted almost every piece, immediately—even running to look them up several times, until I realized these pieces were probably all sold long ago. The sources for each item are indicated, with the prices listed in the captions. Bell draws on auction houses, estate dealers, antiques shops, and private collections, including her own (I assume, in the case of auction houses, the sum named is the hammer price).

The photos—1,000 of them new for this edition—are stunning: the colors true, the details crisp. And overall, Old Jewelry is a handsome book, with classy touches like each page being decorated with an illustrated border running along the top, creating a valence effect. Alas, it doesn’t always read as well as it looks. Typos were noted, some amusing, like “duel” for “dual” or “viola” for “voilà”; some more serious, as when the 19th-century Italian jewelry house Castellani is called “Castillani” (twice!) and Chanel is “Channel.” There one instance of a duplicated paragraph, several duplicated or misleading captions, and I still can’t figure out why a photo of an Art Deco Egyptian Revival watch appears in a section for 1890-1917 pieces.

But why complain? Bell has authored eight editions of this reference book; she must be doing something right. In an introductory note, she writes with love of her adventures in the trade—and how, after 40 years, she is still “excited about old jewelry and the stories it can tell.” Just like me.

Antique jewelry lover Troy Segal has written frequently on the subject for About.com and other sources.