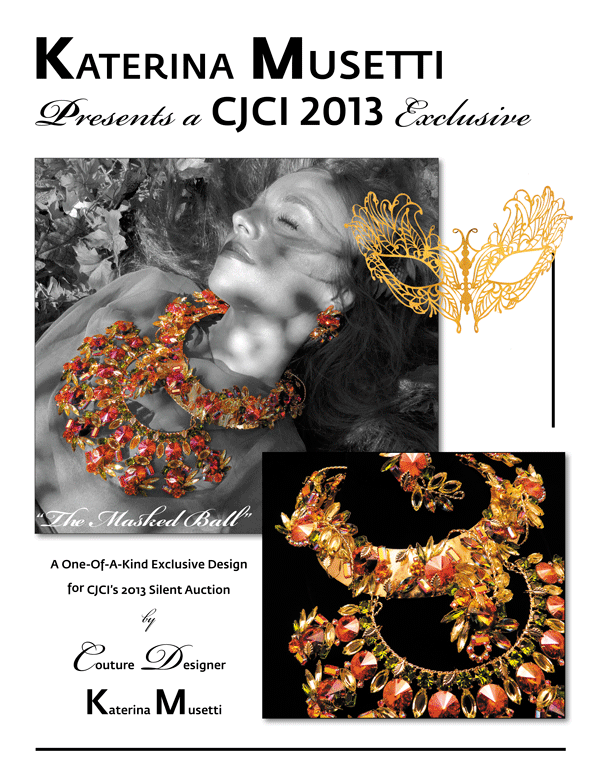

Katerina Musetti Presents a CJCI 2013 Exclusive

September 20, 2013

The Advent of Costume Jewelry and Early Period Copies by Robin Deutsch for CJCI

October 17, 2013Understanding Period Copies

So you’ve saved up your money, you’ve decided that you are finally ready to buy the piece of your dreams – that Marcel Boucher enamel gryphon brooch that you saw on the cover of “Tribute to America” by Carla & Roberto Brunialti. It’s a rare “book piece,” and you see one for sale on a website or online auction as “unsigned MB Boucher.” Even though the pictures are blurry or the size of a postage stamp, and maybe the seller didn’t show the back, you’ve done your research, you know that Boucher is not always signed, or it’s sometimes hard to see the mark. The seller has good feedback or a good reputation. You don’t want to let that beauty get away, so you either pay the asking price or eagerly await your bid or snipe to go through.

You’ve paid $600 (wow, what a steal!) and wait with bated breath for your treasure to arrive. You get the mail, open the package with hands shaking with excitement, and … your heart sinks.

This is a modern day reproduction (not an old “period copy”) of the beautiful Boucher enamel GRYPHON brooch that appears on the front of “Tribute to America” and also in “American Costume Jewelry Art & Industry A-M” on page 50. However, according to Roberto Brunialti, there is a rhinestone version made by Reinad (no surprise, but obviously a period copy), and even lower quality unsigned pieces made of pot metal (yes, there were even copies of copies made during the 1930s and ’40s – see below for Asian Princess examples). CLICK ON IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

You’re disappointed. In person, the piece has none of the true beauty you’ve seen in the book or heard people rave about Boucher. There’s something off with the enamel. You turn it over and it’s pot metal. There is no beautiful, thick, shiny rhodium plating that Boucher used. It doesn’t feel weighty. The findings look cheaper than what you’ve seen on Boucher pieces before. It just looks and feels wrong, even though it looked okay in the picture. What happened?

Welcome to the world of period copies.

To grasp the concept of costume jewelry period copies made during “Golden Age” of the industry c. 1930-1950, understanding the craftsmanship of the originals is imperative. Just as fine jewelers have always copied each other, there were the fabulous imitations of the fine jewelry by the best of the best. American Companies such as Trifari, Mazer, DuJay, Boucher, Ciner, Pennino, all employed designers and model makers from the fine jewelry industry.

Those Who Made the Originals

The best costume jewelers were consummate artists and began their careers making real jewels. They worked for fine jewelry manufactures as designers, model makers, stone setters, etc. and when they lost their jobs due to the Great Depression, it was the burgeoning American costume jewelry industry in which they found employment. Many fled oppression in Europe to find freedom in the United States and brought with them their talent, their tools, and in some cases they even brought their wonderful stash of stones if they could leave with them.

This is an example of an extraordinary copy of a fine jewel made by one of the best costume jewelry companies in the business, Trifari. Their version was designed by Alfred Philippe, but as you can see, it was not an original idea. However, it is extremely rare, all of the stones are breathtakingly handset. There were also brooches that matched the centerpiece. Done in all white, sapphire, emerald (as shown), and ruby just like the original Van Cleef & Arpels piece. The Trifari piece can also be seen in an article on “Junk Jewelry” in Life Magazine in the January 1938 issue although it was made earliest 1936-1937 as the pieces are found both unsigned and marked KTF.

The Van Cleef & Arpels drawing is from the out of print book “Van Cleef & Arpels” by Sylvie Raulet. Although it says the drawing was intended for a 1939 catalog, this was clearly designed before the KTF/Trifari piece. CLICK ON IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

Gustavo Trifari was a platinum fine jeweler in Italy. Alfred Philippe, a Frenchman trained in the art of jewelry design in Paris, worked for William Scheer (the largest American manufacturing jeweler) who produced the New York Art Deco lines for Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, which he designed. In 1930 Gustavo Trifari, Leo Krussman, and Carl Fishel asked him to join Trifari exclusively, and there he stayed until his retirement in 1967. Several Trifari designers over the years came from the best fine jewelry houses including Jean Paris (Cartier) and André Boeuf (Van Cleef & Arpels) who took over as head designer after Philippe’s retirement. Benedetto Panetta, another Italian platinum fine jeweler was a model maker for Trifari during the early 1930s and eventually left to open his own costume jewelry company PANETTA. Renowned for making beautiful imitations of fine jewelry, he said, “If it doesn’t look real, it doesn’t go out the door.” Ruth Kamke of Eisenberg joined Panetta in the 1970s after the closing of Fallon & Kappel, the firm that manufactured Eisenberg’s designs exclusively but she was also asked to join Van Cleef & Arpels early in her career. Sandra Boucher worked for both Harry Winston and Tiffany before and between jobs with Marcel Boucher, and André Fleuridas, designer for Mazer in the 1950s was a fine jeweler and friend of actress Joan Crawford whom he also designed real jewelry for.

Marcel Boucher was not just a designer, but an actual jeweler and model maker early in his career for Cartier. (It’s important to remember that all designers are not jewelers. They can draw the most breathtaking jewel, but it is the model maker who brings the jewel from a two-dimensional drawing into three-dimensional life.)

DuJay, owned by Jules Hirsch and Jacques Leff was the costume jewelry offshoot of 47th Street precious jewelers Hirsch & Leff. And the Ciners were fine jewelers who went into costume jewelry in the 1930s and always worked in sterling silver in their early days, even before World War II made it necessary for other costume jewelers to switch to sterling due to the restriction of base metals needed for the war effort, if they wanted to stay in business.

Looking at the advertisements from 1935-1936 for stores like Saks Fifth Avenue with descriptions such as “copied from a fine jeweler’s model,” is like looking through a time machine. According to the CPI Inflation Calculator (http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl) the buying power (what it would cost in 2013 if new and sold at retail—NOT necessarily what it would sell for vintage in the secondary market which is completely different and this is not to be used as a value guide) is as follows: a Mazer brooch that sold for $10 in 1935 would be $170 in 2013. A DuJay bracelet selling for $75 would be $1,278. A large size KTF/Trifari Clip-mate bracelet that was $45 in 1936 would sell for $750, and a Ciner sterling and paste bangle that sold for $100 in 1938 would be almost $1,700.

To put this in perspective, in 1935 the average annual salary was $1,500, a car was $580 and a house cost $6,300. Clearly, even then, this “costume jewelry” was NOT cheap.

Where there was money to be made, then came the style pirates – the manufacturers that took a well known design by a famous company and made a cheap knock off to be sold at a fraction of the price. Reinad is one of the best known of the vintage style pirates who actually signed their pieces and made them in varying degrees of quality, but most are unknown low-end manufacturers that made unsigned copies. Some of these unsigned pieces were even advertised in newspapers by stores proudly admitting they were copies of a “well known design.”

These priceless photographs depict the less expensive period copies of the Reinad Asian Princess (not shown), which was copied after the exquisite Ruth Kamke original produced by Fallon & Kappel with the early Hattie Carnegie diamond mark (also not shown). Copies like the ones depicted here were made of a top of the line piece by a lower end manufacturer, then copied even more cheaply than the first copy. The copy shown on the left (the least expensive of all) wound up in the 1943 Sears catalog. It sold in the Christmas wish book for $1.07 including tax (in 2013 that equates to about $14.00). CLICK ON IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

Finally, there are the true bane of collectors, which are the real FAKES … out and out reproductions of high end, well known designs with usually a poorly struck signature of the original company, or perhaps a design bearing a famous name never made by that company in the first place. These are different than period copies because they were made new and meant to deceive collectors into paying large sums for something that isn’t authentic. It is the most highly coveted signed pieces that are reproduced such as Trifari and Coro jelly bellies, Eisenberg, the Boucher grasshopper, and the Staret Torch just to name a few. Period copies were just that, copies, usually unsigned, that were sold during the same time frame as the originals or shortly thereafter. They are authentic vintage pieces, collectible and lovely in their own right, but never as valuable as the originals.

Copying the Best of the Best

Marcel Boucher, as I mentioned previously, was trained as an actual bench jeweler and model maker and he understood the engineering of a jewel. He had the talent and the expertise to devise wonderful mechanicals such as his famous Punchinello whose arms and legs moved when you pull on its chain, the cuckoo clock clip that opens to show a little “trembling” bird inside with the words “cuckoo,” and his amazing pelican that surprises you with a fish caught in its mouth. These are the exceptional type of jewels that have sold for four or five figures over the past 10-15 years Made in small quantities and truly rare, they are the type of pieces collectors would sell their souls for.

The original pavé piece on the right was also done by DuJay with the pears in red and yellowed speckled enamel. That version has been found as a latter day reproduction/fake signed Weiss as well. (Weiss never made such a thing, nor the other Weiss enamel fruits that are out there in the same coloring). This is probably the most copied DuJay design next to their rickshaw. CLICK ON THE PHOTO TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

The model maker is the one who actually interprets the design, the blueprint if you will, to bring a costume jewelry drawing, or rendering, to life. Sometimes it is too expensive or even impossible to translate a design into an actual jewel, even a non-precious one. Many of these companies went through the long and expensive process of patenting their designs to legally protect them. This could take up to 3 months although during the war years sometimes it took a year for a design patent to be approved, and on certain utility patents for mechanisms, the wait was even longer. (A design patent for how something looks had the duration for 3 ½ years. A utility patent for how something works, such as an ear clip finding, clasp, brooch mechanism, etc. was good for 17 years.) It’s estimated that patents cost about $40-$60 back then. With so many models being produced year after year, that was a lot of money for a company to invest to protect their designs.

Unfortunately, by the time the patent was approved, or in the process, the jewelry was already in production (hence PAT PEND or “patent pending” if approval was not received at that point), or photographed for an advertisement for a store and hitting the newspapers and fashion magazines. These companies typically had one season, and then they were on to the next. There are exceptions. Some Trifari pieces are marked with their earlier KTF mark and later as Trifari. Some models were manufactured within a year or two of each other, but some designs were reissued in the 1950s and 1960s. Two of Coro’s most famous designs such as the Coro Quivering Camelia Duette was made in the 1930s through the 1940s both with dress clip mechanisms and pinclip (fur clip) mechanisms, and their Carmen Miranda bracelet made in the 1930s-1940s are found unsigned or marked Coro or Corocraft, in base metal and sterling, all the way up to the 1960s marked Vendome. Many smaller companies such as DeRosa, Pennino, DuJay and Boucher had very few patents compared to a company as huge as Coro who has the most patents issued to a costume jewelry company, with Trifari running second.

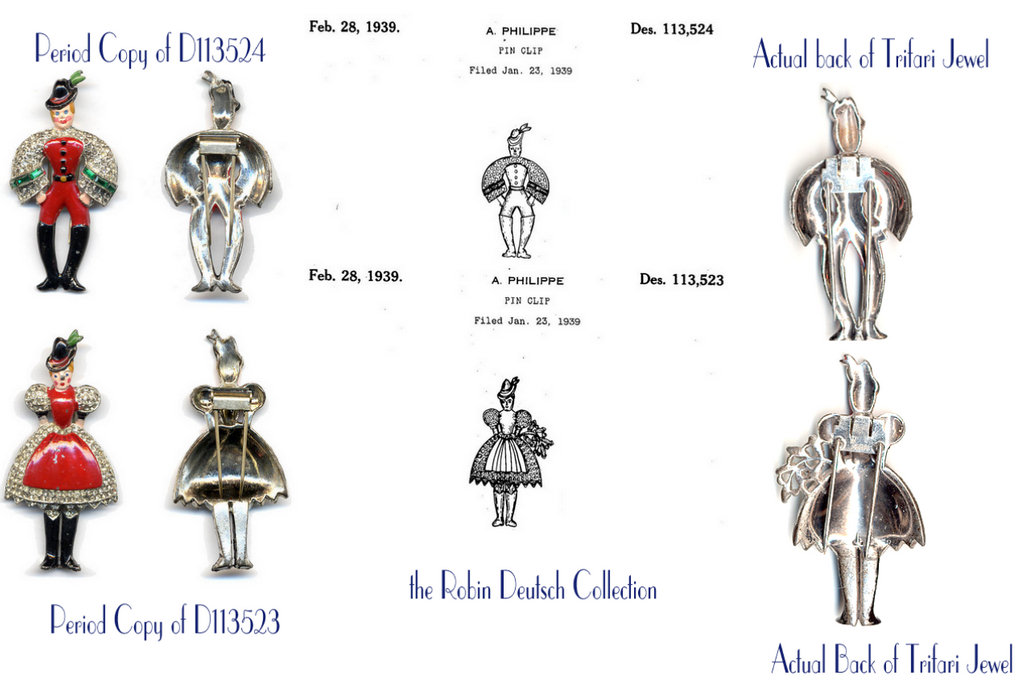

Lower quality versions of this Swiss couple at first glance look very much like Trifari’s patented Peter and Helen, but many different period copies of these were made (including a pot metal version of Helen holding the bunch of flowers). They were obviously a very popular motif. A number of things stand out about the pair shown at left are: 1) They are not signed. 2) They have no patent number or PAT PEND that would be present on the Trifari pieces. 3) The woman copy is not carrying flowers shown in the in the Trifari version. 4) They do not have characteristic Trifari signed furclip mechanism as shown on the originals at right. The authentic ones also came in another color version with blue suits and dresses. These are actually very nice period copies, but they should sell for a fraction of the authentic Trifari pieces. CLICK ON IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

So here you have companies that had some of the greatest and most talented designers working for them, the best model makers, the most gorgeous and complicated designs, the best quality components and the best workmanship. And what happens? Someone comes along, buys (at retail) that gorgeous signed Hattie Carnegie Asian Princess that Ruth Kamke of Fallon & Kappel designed, or a stunning piece like the Boucher gryphon, an exquisite piece of DuJay or Trifari, a fabulous Mazer bejeweled mask, takes out the stones, sticks it in a mold, and makes a copy.

Let’s be very clear about one thing. No one copies another company to make a more expensive and better version than the original. They look for ways to make a copy that on first glance looks like the original design, but on closer inspection is always less beautiful, less well made, using cheaper components, fewer stones, and lower quality enameling to make it as cheaply as possible to cash in on the reputation and designs of the higher end manufacturer. And here you have it. Costume jewelry was BIG business, and there were thousands of companies vying for these precious dollars.

Robin Deutsch has been a jewelry historian and collector since the 1990s. She specializes in American and European costume jewelry, anything from Edwardian to made yesterday. She is a member of many fine and costume jewelry organizations, and she also has her own website on the German jewelry company Knoll & Pregizer which she published in 2009, bringing to the forefront the name and history of this company that was lost to posterity. She was also a lender to the museum exhibit “Finer Things” at Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens, Akron, Ohio, April-October 2012.